Lately, as I’ve been wrapping up the dissertation and crafting the conclusion, I’ve been thinking about some of the main themes of my work.

I think the main theme I’ve come across again and again is the erasure of women and their work. It wasn’t just in Houston, and it wasn’t just in the postwar period, but it is incredibly blatant in both.

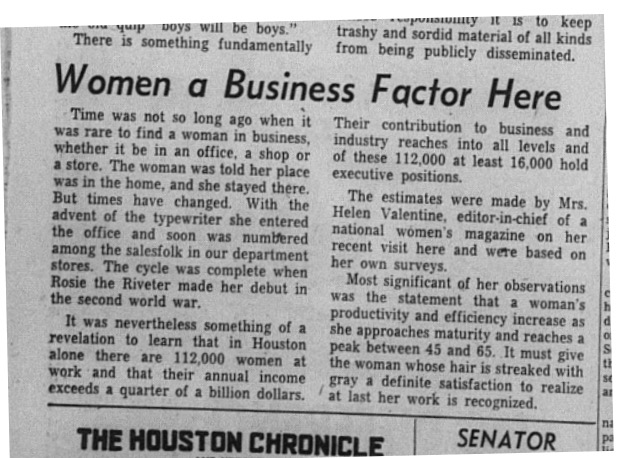

Take this article from the Houston Chronicle in 1954.

The women of Houston proved to be like their peers elsewhere: “unexceptional women,” as Susan Ingalls Lewis refers to women entrepreneurs, who were engaged in the economy in multiple sectors. City commentators continued to find women’s ownership of enterprises and participation as workers astonishing into the 1950s, as this article shows.

Enterprising women might have been “unexceptional,” but they were also relatively underground and novel.

Take City Cafe.

Myrtle Choate filed the first confirmed business license for City Café in 1946, six years prior to the estimate of the current proprietors, following a trend of more women opening businesses across the nation, supported by a federal government eager to move women out of industrial jobs as men returned from their positions in the military. Following Choate, several other women owned City Café into at least the 1960s, reflecting the high-turnover in the restaurant industry.

Although the current owners of City Café have no connection to Myrtle Choate or the other female owners of City Café at mid-century, upon seeing that City Café was still open at the same location, I called to see if perhaps there was any knowledge of the former owners or any way of tracking down more information. A few other Houston restaurants, such as Pizzitola Bar B Cue, despite changing hands, continue to retell the legacy of those who founded the establishment, using the information to establish deep ties to their community and assure patrons that the new owners will continue and honor what makes the establishment good. The manager on duty informed me that, although the owners were not available for me to talk to, as far as she knew, no woman had ever owned City Café or been involved in the direct management of it. As I sputtered about the city records that proved multiple women had been involved in owning the restaurant in its early years, the manager continued to politely and firmly state that a woman owning City Café was not possible. It had been ran by men for several decades, and it is true that a line of men owned the restaurant beginning in the 1970s, so, for the manager and many patrons, the history of City Café is dominated by male proprietorship. Myrtle Choate and the multiple women who followed her had been erased.

This process was repeated over and over. Exceptional women, like Ninfa Laurenzo, are remembered by Houston, but the Myrtle Choates are invisible. I hope that my dissertation removes that invisibility, asserting that Houstonian women were instrumental to the economy of the booming city and, in turn, outside forces like gender norms, the economic nature of the Sunbelt, Cold War ideology, and segregation shaped the experiences of individual women as they sought to establish a proprietorship and carve out an economic position for themselves.